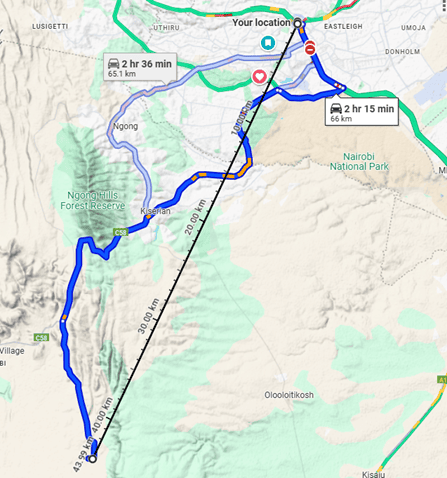

As the bird flies, Loodariak is less than 45km from the heart of Nairobi, and 20km from the nearby town of Kiserian. By road, the journey is a lot longer. Enroute, you must contend with one of the worst-managed traffic situations in the world, the never-ending gridlock that exists between Ongata Rongai and Kiserian, two towns that together with Ngong’ Town take the southern side of the spillover arising from the suburban inadequacies that bedevil Nairobi. Driving on from Kiserian, a rapid descent towards Lake Magadi starts. A little after Ole Polos, branching off is a dusty road that runs to Loodariak, and all the way down to Torosei near the border with Tanzania.

The dusty road is extremely rocky in sections, but otherwise motorable for the most part, albeit at a slow pace. It is a scenic route, with a 300m high ridge running the entire length of the road on one side. The other side undulates, with the elevation tending lower and lower for tens of kilometers on end. All the little settlements are on this side of the road.

This may indeed happen soon. The thing with Nairobi is that one moment, you would be immersed in the hustle and bustle of the big city, and the next, driving off a few kilometers in one direction, a few turns to the left or right, and you find yourself in the midst of undisturbed nature. Loodariak was one such place, fifteen or so years ago, when I first visited.

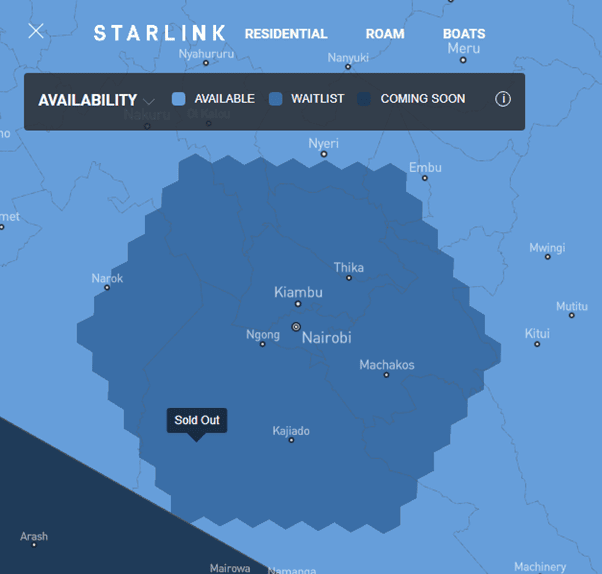

This is the kind of place that would immensely benefit from Starlink coverage. I have expressed in the past that the approach taken by Starlink in Africa was flawed. Now, there are certain telecommunications use cases for which Starlink would legitimately be the best solution. These are in situations such as aircraft in the sky, sailing ships in the ocean, remote islands, sparsely populated rural areas, traveling vehicles, a mine in the middle of the desert, your holiday home in the countryside etc. A satellite service works best when it is a lightly loaded niche product to which a few subscribers connect at a time. This is indeed the approach that Starlink has taken in the USA and Europe, focusing their marketing for use cases in the rural areas, pointedly staying away from the cities.

In Africa, they have taken a different approach. There was a deliberate push to market the Starlink service to the mass market, specifically to individuals and businesses in the dense urban areas. Starlink may have observed the inherent failings of the African rural economy and the unlikelihood of it generating sufficient demand to sustain their business model. This realization likely influenced their decision to target the urban markets instead, where disposable incomes and demand for connectivity are significantly higher. However, this approach not only undermines the original promise of satellite broadband, to connect remote and underserved areas, but also exacerbates congestion, engendering a first come first served, best effort situation, which leaves the rural users unable to benefit from the service.

Starlink may have recognized that rural users in Africa would find their services unaffordable, so they may have strategically focused on the dense urban areas in Africa where the demand could drive quicker sales. This despite the inherent challenge that Starlink faces, its intrinsically and insolvably insufficient capacity to adequately serve the dense urban market.

A few months ago, I had predicted that this approach was going to yield disappointment among the enthusiastic customers. I did some rough calculations, which I outline below. Admittedly a few figures may be off because I am not privy to the traffic modelling by Starlink or their traffic usage and scheduling policies.

Elon Musk in a company update early this year, indicated the intention to have 6600 satellites in orbit. The number and data fabric capability of the satellites are:

- 4,400 V1 Satellites, each with capacity 20Gbps. These are already deployed.

- 2,200 V2 satellite, each with capacity of 40Gbps. The deployment of this is ongoing.

This will make a total of 6600 satellites. With the throughput capability indicated above, the total capacity of the Starlink system would be 250 Tbps. The satellites are meant to be uniformly distributed around the global sky, leading to the assumption that every location on the surface of the earth has an equal probability to get good service from a Starlink satellite. The reality though is that due to the orientation of the satellite orbits, subscribers at the mid to high latitudes will usually have more Starlink satellites available to serve them than the subscribers at the lower latitudes. Effectively, by dint of design, the guys in Europe and North America will receive better service from Starlink than we at the Equator. But that is a story for another day.

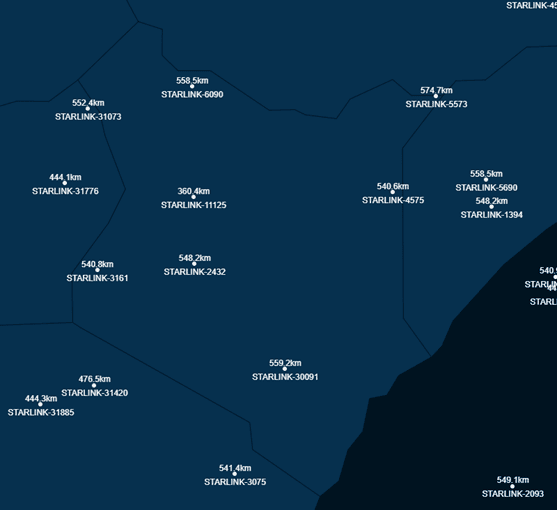

We want to keep our conversation simple, so let’s keep going with the assumption that you in Kenya will still have the same number of satellites serving you as one in Montana, USA. The earth’s geoid surface area is 509,600,000 square km, while the area of Kenya is 580,370 square km. This means that approximately 0.114% of the earth’s surface is within Kenya. By estimation therefore, at any one time, we would have 2.5 of the 40Gbps satellites and 5 of the 20 Gbps satellites zooming over Kenya.

The snapshot of the real time satellite proves this, we currently have not more than 10 satellites available to serve the geographical area of Kenya.

The capacity available to Kenya on Starlink therefore would be somewhere in the neighbourhood of 200Gbps.

200Gbps shared for a whole country would be okay if the service was offered for the use cases I earlier mentioned: to soldiers who have set up base near the Somalia border, to the people manning the oil mines and wind energy plant in Turkana, ships berthed off the port of Mombasa, your cottage in a remote village, your yacht in Lake Victoria, and so on. By my estimation then, the number of people in Kenya that could be satisfactorily supported by the Starlink as currently configured could not exceed 30,000. I bravely predicted that the drive to sell Starlink as an alternative to Safaricom Fibre, JTL Fibre or Zuku, targeting the mass market in dense urban areas, was going to end in tears.

200 Gbps is lower than the capacity that Safaricom can avail to a single population centre in Kenya if needed.

It did not take long. Already, Starlink service in the Nairobi region, which includes Loodariak is congested, sold out.

Starlink is now asking the potential subscribers to wait for capacity expansion in its global network before they can join and benefit from Starlink service. However, expanding the capacity of satellite network is far from a straightforward affair. By design, satellite technology does not lend itself to rapid or easy capacity scaling.

One approach to capacity expansion involves adding more satellites. The Starlink plan was to deploy up to 32,000 satellites, which when complete will increase overall capacity fivefold.

The second approach is to enhance the design of the satellites themselves to enable greater capacity carried per satellite. This plan appears to be underway, as SpaceX already requested the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to modify the operational parameters of its next-generation satellite system. The company sought permission to lower the altitude of these satellites, allowing them to operate closer to Earth, and to use authorized frequencies with greater flexibility. SpaceX argued that these changes would enable fiber-like broadband speeds, faster latency, and ubiquitous mobile connectivity, thereby helping to bridge the digital divide for billions of people. this story sounds familiar though, as it was exactly the same words that were used when they were advertising Starlink service in Nairobi months ago.

These next-generation satellites, which are significantly larger, promise a tenfold increase in bandwidth. However, achieving this vision requires regulatory approvals not just from the FCC but also from authorities in every country where they plan to offer their services.

Even with these advancements, boosting the number of satellites to 32,000 and increasing the capacity of each satellite tenfold, it will still be insufficient to meet Africa’s connectivity needs if Starlink continues its unethical practice of targeting the dense urban areas as its primary market for satellite broadband. This strategy undermines the core value of satellite technology: serving remote and underserved areas that lack alternative connectivity options.

A broadband user in Loodariak cannot currently benefit from Starlink’s service because the network is congested by Nairobi users. This situation could have been avoided if Starlink had not unethically marketed and sold its services to users in densely populated areas in Nairobi and its suburbs which already have service from FTTX, 4G and 5G FWA and Mobile. Starlink may not have taken very seriously the nature of the settlement patterns in East Africa, where the distinction between urban, suburban and rural areas is often blurred. Underserved Loodariak, for instance, is only 45km from the heart of Nairobi. The satellite footprint serving Loodariak, the expansive ranches of Kajiado, the other side of Machakos etc. is the same one that is congested by the office blocks and high-density apartments of Nairobi city.

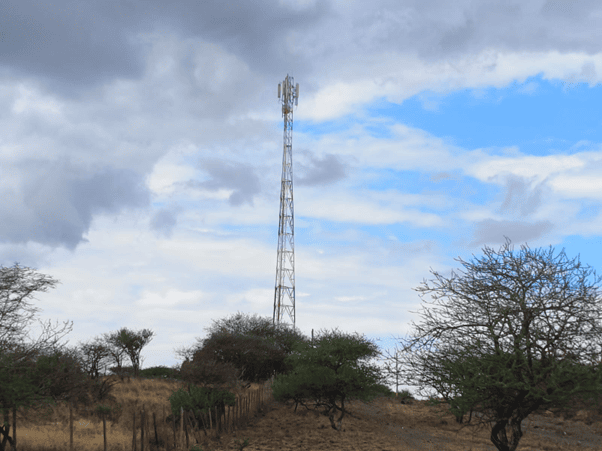

Back in 2008, Loodariak had no grid electricity, no cellphone coverage and little evidence of modern infrastructure. Along the route, you were more likely to encounter hundreds of goats ranging unattended than you would the lone herdsman watching them. If your car broke down, you had to walk to Magadi road to seek help. Today, you just need to sit beside your car for 30 minutes, and soon enough a young man on motorcycle will come riding along. A Kenya Power three-phase line now runs all the way to Loodariak Centre, since 2012 thereabouts. The centre itself boasts a primary school, a secondary school, a dispensary, at least three churches and at least one decently sized hotel. Perhaps most notably, there’s now a fully operational mobile telecom tower site offering Safaricom 4G, 3G, and 2G connectivity.

This is development, on the face of it undeniable, visible and tangible, and could be said to be impactful.

In 2020, Loodariak was one of the unserved and underserved sublocations earmarked for subsidy under the Universal Service Fund (USF) by the Communications Authority of Kenya. The goal was to facilitate infrastructure rollout to ensure coverage for at least 80% of the sublocation's population and 60% of the sublocation's geographical area. This initiative appears to have had some success, significantly improving connectivity in the area. It would appear therefore that as concerns the initiative to extend broadband coverage to the rural areas, previously unserved and underserved, at least with regard to Africa, the regulators and the mobile network operators are making strides towards accomplishing the job, while Starlink expends energy on a job that isn’t theirs.